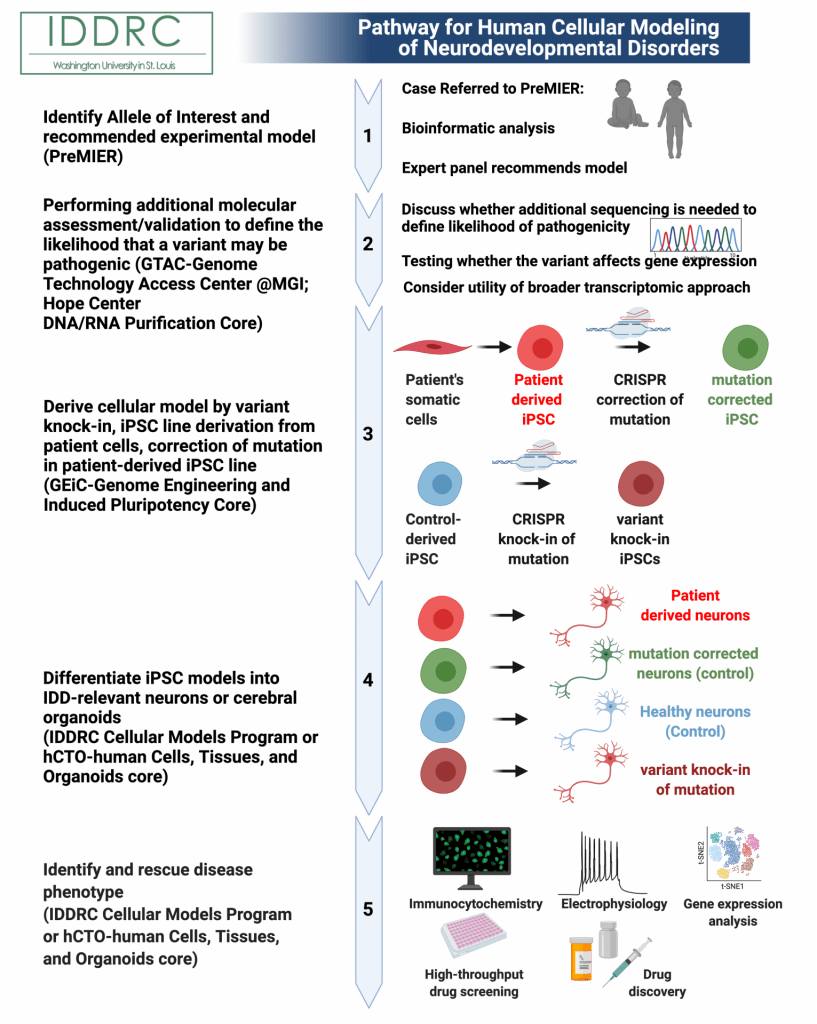

A bird’s eye view of the generation and characterization of novel mouse and cellular models of potentially pathogenic variants

1) Identify allele of interest and receive experimental model recommendation. Submit a patient variant to the Precision Medicine Integrated Experimental Resources (PreMIER) Platform. A panel of experts will direct clinicians and researchers to appropriate model systems and resources at WUSTL, to facilitate progress in our fundamental understanding of biology and human health and disease.

2) Performing additional molecular assessment/validation to define the likelihood that a variant may be pathogenic.

2A) Discuss whether additional sequencing is needed to define likelihood of pathogenicity. First steps to determine whether the variant is likely to be contributing to the patient’s clinical phenotype may involve sequencing biomaterials from the parents, to determine whether the variant is inherited or de novo (if unknown). For example, if the parents carry the variant and are not clinically affected, the variant is less likely to be pathogenic in the affected subject.

2B) Testing whether the variant affects gene expression. It is then important to determine when and where the gene is normally expressed and whether production of the gene product has been affected by the variant. This often involves obtaining biomaterials from the patient and determining whether levels (or size) of the gene product’s RNA or protein are altered. This assessment is tuned to the type of variant involved and whether the variant likely causes a change in the levels of mRNA/protein that are made, or may instead alter function in some other way (e.g. mis-localization of gene product in cells or altered function of a missense variant). This assessment can often be done in more readily obtained biomaterials (patient-derived fibroblasts or blood) if the gene is expressed in these tissues. If expression of the gene is limited to a tissue like the developing brain, this assessment may require derivation of an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line and differentiation of that line into a cell type that expresses the gene (e.g. neurons or glia for cases of intellectual and developmental disorders).

2C) Consider the utility of a broader transcriptomic approach. In some cases, either the original biomaterials or iPSC-derived lines generated from the patient might then be additionally utilized for a more comprehensive transcriptomic analysis by RNA-seq, to determine more broadly how the variant has altered gene expression.

3) Building a human cellular model. There are several options for building a human induced pluripotent stem cell model of a pathogenic gene variant:

3A) Proband derived with correction approach (PD/PD-C cell line pair). Since genetic background strongly influences the phenotypes seen in human cellular models, experiments are ideally controlled by work with pairs of isogenic iPSC lines with versus without the suspected pathogenic mutation. One such pairing can be obtained by deriving iPSC lines from patient biomaterials (ideally deriving 3 or more clonal lines per patient, to control for differences between clonal lines). Then, if possible, CRISPR-based genome engineering is used to correct a potentially pathogenic variant, to generate a proband-derived (PD) and proband derived and corrected (PD-C) model pair for parallel phenotyping.

3B) Variant knock-in approach (WT/VKI cell line pair). The genetic background of individual patients varies substantially and often modifies the phenotypes obtained, likely modifying both the clinical phenotype present in the patient and the associated phenotypes seen in patient-derived cellular models. Therefore, using CRISPR to engineer the potentially pathogenic gene variant into an age and sex matched control iPSC line (derived from an individual known to have no clinical phenotypes) can segregate the effect of the variant from potential genetic background modifiers. For intellectual and developmental disorders, the Cellular Models Unit carries several such control iPSC lines for variant introduction. An isogenic pair of lines with and without knock-in of the pathogenic variant (wild type control WT and variant knock-in (VKI)) often provides an ideal starting point for modeling the pathogenicity of a potential gene variant and associated cellular and molecular phenotypes.

3C) Assessing effects of gene knockdown in parallel (CRISPRi knockdown). Since many pathogenic variants act by reducing gene activity, if both the variant and gene are of unknown significance, it can also be beneficial to derive tools to knock down the expression of the gene. This enables us to determine whether loss of function results in phenotypes that resemble the effects of the variant and to study requirements for the particular gene. We generally use the CRISPRi approach for this purpose. The Cellular Models Unit carries human pluripotent stem cell lines expressing an enzymatically dead form of Cas9 coupled to the KRAB repressor; introduction of a guide RNA targeting the promoter of the gene of interest into these lines achieves effective gene knockdown and can be used to study the effects of deficiency.

4) Cellular phenotyping workflow. The phenotyping workflow is customized, depending upon particulars of the gene, variant, and clinical phenotype.

4A) Define optimal cellular modeling strategy. An initial consultation with the WUSTL Cells, Tissues and Organoids core (for non-intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) cases) or the IDDRC’s Cellular Modeling Program (for some IDD cases) should be conducted. This will define the most appropriate cellular modeling protocols to follow and potentially expert collaborators at WUSTL who can facilitate differentiation of iPSCs into an appropriate cell or tissue type for modeling. For modeling IDDs, cortical excitatory or inhibitory neurons or cerebral organoids are often ideally suited for modeling.

4B) Perform standard QC assays on the human pluripotent stem cell line model pairs. Since clonal human pluripotent stem cell lines can exhibit different properties, it is important to conduct key assays in at least two independent clonal lines for each model type (e.g. VKI, PD, PD-C). A first step is to validate the quality of new iPSC lines through standard quality control assays. These assays can be done by GEiC, by the WUSTL Pathology laboratory, or in the PIs laboratory and typically involve:

- validating the identity of the lines, by STR testing relative to the initial source of patient biomaterials (e.g. for PD/PD-C lines)

- regular mycoplasma testing, to ensure absence of contamination

- cytogenetic analysis to ensure that lines have a normal karyotype

- assessments to ensure that the lines are pluripotent and capable of multi-lineage differentiation (minimally staining for markers of pluripotency, assessment of colony morphology, and testing whether clonal lines differ in their capacity to differentiate into the desired cell or organoid type.

- sequencing to ensure that the clonal line carries the mutation of interest.

4C) Determine how the variant affects production of the gene transcript and protein. If not already determined above (in 1B) this will be an important step to validate that the model does affect the expression or potential function of the gene in question, enabling further analysis.

5) Define optimal initial set of phenotyping assays. The next aspect of this consultation will consider in combination the patient’s clinical phenotype, the normal temporal and spatial expression profile of the gene during human development, and the normal function of the gene, if known. This consultation will guide the selection of an initial set of phenotyping assays and timepoints for making assessments. A goal of the initial phenotyping assays is to survey when phenotypic differences are observed and what the nature of these changes are in general. This typically involves determining whether the phenotypes are related to altered basic cellular physiology (changes in proliferation, senescence, apoptosis, metabolism in the pluripotent iPSCs), altered development (specification, differentiation–timing or efficiency), altered later, functional properties (migration, morphology, functional readouts), and/or altered organoid structural organization/complexity. Please see the range of phenotyping assays that can be conducted by the IDDRC’s Cellular Modeling Program for further details at the links below.

Useful Links

- PreMIER

- GTAC Genome Technology Access Center @MGI

- Hope Center DNA/RNA Purification Core

- Genome Engineering and Induced Pluripotency

- IDDRC Cellular Models Program

- Human Cells, Tissues and Organoids (hCTO)

- Assessment of neuronal function

Estimated Budget for Cellular Modeling

- Isolation and testing for expression of the mRNA/protein product of the gene <$1000

- A full RNA-seq analysis of this sample $1-2,000

- Derivation of an iPSC line including differentiation and analysis $6-7,000 per line

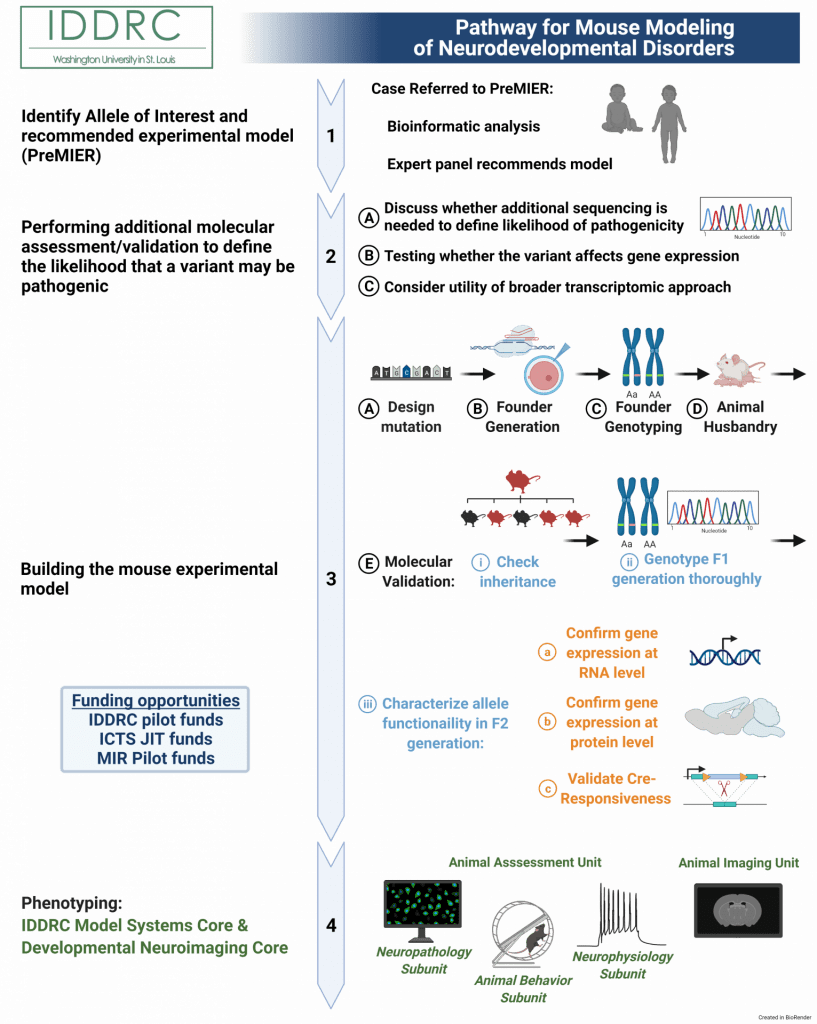

1) Identify allele of interest and receive experimental model recommendation.

Submit a patient variant to Precision Medicine Integrated Experimental Resources (PreMIER) Platform. A panel of experts will direct clinicians and researchers to appropriate model systems and resources, to facilitate progress in our fundamental understanding of biology and human health and disease.

Contacts

- PreMIER

- Kristen Kroll, PhD (kkroll@wustl.edu)

- Angela Bowman, PhD (abowman@wustl.edu)

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Identify variant to submit to panel; decide to move forward with recommended model

2) Performing additional molecular assessment/validation to define the likelihood that a variant may be pathogenic

A. Discuss whether additional sequencing is needed to define likelihood of pathogenicity. First steps to determine whether the variant is likely to be contributing to the patient’s clinical phenotype may involve sequencing biomaterials from the parents, to determine whether the variant is inherited or de novo (if unknown). For example, if the parents carry the variant and are not clinically affected, the variant is less likely to be pathogenic in the affected subject.

B. Testing whether the variant affects gene expression. It is then important to determine when and where the gene is normally expressed and whether production of the gene product has been affected by the variant. This often involves obtaining biomaterials from the patient and determining whether levels (or size) of the gene product’s RNA or protein are altered. This assessment is tuned to the type of variant involved and whether the variant likely causes a change in the levels of mRNA/protein that are made, or may instead alter function in some other way (e.g. mis-localization of gene product in cells or altered function of a missense variant). This assessment can often be done in more readily obtained biomaterials (patient-derived fibroblasts or blood) if the gene is expressed in these tissues. If expression of the gene is limited to a tissue like the developing brain, this assessment may require derivation of an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line and differentiation of that line into a cell type that expresses the gene (e.g. neurons or glia for cases of intellectual and developmental disorders).

C. Consider utility of broader transcriptomic approach. In some cases, either the biomaterials or iPSC-derived cells might then be additionally utilized for a more comprehensive transcriptomic analysis by RNA-seq, to determine more broadly how the variant has altered gene expression.

Contacts

Depending upon what needs to be done (and from which biomaterials), clinician can collaborate with IDDRC Cellular Models Unit, use a commercial platform for Sanger sequencing, or collaborate with any lab with wet bench activity to perform RTqPCR to detect expression levels (and mutation related change) in biomaterials from patient vs controls

Approximate Cost

$2,000-$3,000

3. Building a mouse experimental model

Current technology for building a mouse experimental model uses the CRISPR-Cas9 platform to perform precise gene editing, including point or frameshift mutations, and conditional and inducible models.

A. Design mutation.

This step requires the known sequence of the pathogenic variant. If the Investigator does not have the required genetic expertise in their own lab to design the mutation in mouse, services provided by the GEiC can complete the entire process from design of the mutation in mouse to sending validated vectors off to another core for generating the ‘founder’ mouse for the mutant line by delivery of genome editing reagent to mouse eggs.

The very first step is to design a strategy for altering the homologous or orthologous gene sequence in the mouse to that of the pathogenic variant sequence. The GEiC can provide this for the Investigator, including a full bioinformatics workup for the target. The current strategies typically entail using CRIPSR/Cas9 tools to introduce the single nucleotide (point) mutation or insertion or deletion (frameshift) mutation. GEiC will test the functionality of the strategy in cell culture to confirm before assembling the required reagents for generating the mouse. This includes oligos and/or AAV plasmids for inserting the patient mutation, gRNAs to target cutting the genome, and Cas9 enzyme. GEiC will also develop and benchmark in cell culture a strategy to confirm correct genome targeting via PCR and sequencing.

Contacts

Xiaoxia Cui, PhD, GEiC Director (x.cui@wustl.edu)

Approximate Costs

Varies based on individual project needs, roughly $1,000-$2,500

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Confirm design

B. Zygote injections with electroporation & Founder generation.

Following successful design of the strategy, the next step is to introduce the pathogenic variant mutation in the mouse genome. This is done by delivering the donor templates into mouse zygotes using adeno-associated viral (AAV) injections coupled with electroporation to deliver the CRISPR complex and gRNAs. This step can be performed at either the Transgenic, Knockout and Micro-Injection Core or the Mouse Genetics Core. GEiC will partner with these cores to arrange delivery of the required reagents, and can also provide genotyping of resulting ‘candidate’ founder mice (below). A typical day of injection may involve 100 mouse eggs, yielding up to 30 viable animals, of which 5-20% may have targeted, depending on the complexity of the project. Complex projects often require more than one day of injection to assure a founder.

Contacts

- Transgenic, Knockout and Micro-Injection Core, J. Michael White, PhD, Director (white@wustl.edu)

- Mouse Genetics Core (MGC), Mia Wallace (mia@wustl.edu)

Approximate Costs

Varies based on individual project needs, roughly $1582/session (MGC)

C. Founder genotyping.

This stage is crucial for identifying potential success of integration of the pathogenic variant mutation into the mouse genome from the candidate founder mice. Samples of tail DNA from successful live births at the previous step are assayed at this step to test for successful of genomic editing, via PCR combined with sequencing techniques, using positive controls from cell line DNA from 3A. Such characterization can be performed by a molecular biologist in the Investigator’s lab, or the GEiC. The interpretation and decisions based on the data for which founder mice to take forward, however, will remain the responsibility of the Investigator.

Contacts

- Xiaoxia Cui, PhD, GEiC Director (x.cui@wustl.edu)

- Mouse Genetics Core (MGC), Mia Wallace (mia@wustl.edu)

Approximate Cost

- $250-500/96 well plate (GEiC)

- $4.01/rxn (MGC)

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Identify successful integration of variant or loss of gene product. GEiC or MGC will provide guidance through their collaborations.

D. Animal husbandry.

Once founder mice are identified, they need to be maintained. This includes breeding, weaning, mouse monitoring, and tissue biopsies for genotyping, as well as record keeping. This can be done in-house by the Investigator or through the Mouse Genetics Core as fee for service.

Contact

Mouse Genetics Core (MGC), Mia Wallace (mia@wustl.edu), https://mgc.wustl.edu/services

Approximate Cost

$1.29/cage/day + $4.01/rxn genotyping, DCM per diems

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Direct the MGC on the fate of the animals.

E. Molecular validation.

Once genotype positive founders for the line is established, each will need to be taken forward to evaluate whether the mutations are heritable to subsequent generations and therein have the intended effect on the target gene. This step is crucial for confirming the experimental model is successful and moving forward with study of the variant.

i) Check inheritance. Depending on steps above, between ~ 1 to 10 different genotype positive founders will be available for breeding to establish independent lines line. The first step in winnowing the group to the final best line is to establish inheritance from the potential founders. This step involves breeding and genotyping. This is usually performed in the Investigator’s lab, however, the Mouse Genetics Core (MGC) can provide both of these services for associated costs. The Investigator, however, will need to interpret inheritance patterns. GEiC can assist in the selection of potential founders to breed.

Males can breed to multiple females at the same time. Thus, males can produce multiple litters per three-week gestational period while females can only produce one litter per three-week gestational period. Therefore, if available, it is most efficient to move forward with potential male founders at this point, typically breeding 2-4 different candidates and keeping the remaining genotype+ founders in reserve. It is important to breed to true wild types of the background strain (usually C57BL/6J). These can be purchased from Jackson Laboratories (https://www.jax.org/strain/000664).

If the mutation is autosomal and non-mosaic, then each male should pass the mutation to 50% of the pups in each litter. GEiC, MGC, or the Investigator’s lab can genotype the progeny. Any progeny that does not inherit the variant mutation can be euthanized. The remaining, variant-harboring progeny is the F1 (first filial) generation.

Contacts

Mouse Genetics Core (MGC), Mia Wallace (mia@wustl.edu)

Approximate Cost

$1.29/cage/day + $4.01/rxn genotyping, DCM per diems

Clinician/Investigator

Will need a bioinformatician to analyze RNA-seq data

ii) Genotype F1 generation thoroughly.

Since founder animals may be cryptic mosaics, the F1 generation is truly the generation at which the line is firmly established: all F1 generation is truly the founder generation. All subsequent animals will be produced from these animals. Thus, the inheritance of the mutation in this generation needs to be unequivocally confirmed. This is done through thorough genotyping using PCR and sequencing techniques. This can be performed by a molecular biologist in the Investigator’s lab, however, GEiC, GTAC, and the Hope Center DNA/RNA Purification Cores are available resources on campus for several of these steps. The interpretation and decisions to move forward, however, will remain the responsibility of the Investigator. In addition, bioinformatics skills will be required to analyze and interpret sequencing data.

Both the 5’ and 3’junctions surrounding the mutation need to be confirmed as correct using PCR strategies. Once that is confirmed, the entire locus in which the mutation was introduced needs to be sequenced. It is particularly important at this step to confirm the exons are correct. GEiC is a great resource on campus for this stage. Mice that successfully pass these validation procedures can now breed to true wild type mice to generate the F2 generation.

There is always a risk of off-target effects of the gene editing processes. However, the odds of co-inheriting with the locus of interest is really low. Therefore, by the F3 generation, any off target effects will have been bred away. Steps 3Ei and 3Eii will take approximately 9 weeks to complete, based on the gestational duration of mice (3 weeks).

As founder and F1 genotyping may have been PCR followed by sequencing, at this time it will become more cost-effective to develop more simple PCR-only based methods to have a single simple genotyping assay for subsequent generations. For example, for point mutations, presence of the mutation can be determined via genotyping allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) procedures. See Genotyping Primer Design and Protocol Appendix for detailed protocol for primer design, DNA extraction methods, PCR steps, and gel electrophoresis instructions for designing and optimizing allele-specific PCR for detecting point mutations. This is not currently offered as a service, but perhaps could be discussed with GEiC.

Contact

- GEiC, Xiaoxia Cui, PhD, Director (x.cui@wustl.edu)

- Hope Center DNA/RNA Purification Core, Carlos Cruchaga, PhD, Director (cruchagac@wustl.edu)

Collaborate with any lab with wet bench activity.

Approximate Costs

- $200 + $100/sample (GEiC)

- $16/sample (Hope Center DNA/RNA Purification Core)

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Will need a bioinformatician to analyze RNA-seq data

iii) Characterize allele functionality in F2 generation.

Now that the model has been established as genomically correct and transmitting, the model mutation can now be characterized for functionality. (Note that some steps may require embryonic tissue, extraction of which will kill the dam. Therefore, it is important to do this when more there are more than 6 well-validated mice in the F1 or F2 generations designated for breeding, so you do not lose mice that you need to continue the line). Typical mutations involving stop-gain are predicted to decrease RNA and protein levels, though missense mutations may also have such effects, so all should be assessed. Overall, it is important to distinguish the effects of the mutation both at the RNA and protein levels because adaptive mechanisms may exist for the locus of interest such that mRNA from one allele is enough to produce wild type levels of protein translation. It is also important at this stage for the Investigator to determine what tissue types should be measured (e.g. whole brain, specific brain regions if expression is limited, peripheral tissues, etc), depending on where the gene is expected to be expressed. Set up for this experiment would typically involve crossing pairs of heterozygous animals to produce litters with heterozygote, homozygote, and wildtype animals in the expected ratios (2:1:1) that can be evaluated biochemically. In addition, data across litters should be summer to look for deviations from expected ratios as indications of embryonic lethality, decreased viability, or impaired fertility.

iiia) Confirm gene expression at the RNA level – qPCR or sequencing.

This step will inform is the mutation reduces gene expression at the RNA level in the progeny above. This requires reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) which allows for quantitative measurement of RNA levels (in contrast with genotyping PCR which is a presence or absence assay). For loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutations, this step will validate if the function was altered in the correct direction.

This can be performed by a molecular biologist in the Investigator’s lab, however, GEiC, GTAC, and the Hope Center DNA/RNA Purification Cores are available resources on campus for RT-qPCR. The interpretation and decisions to move forward, however, will remain the responsibility of the Investigator.

Contacts

- GEiC, Xiaoxia Cui, PhD, Director (x.cui@wustl.edu)

- GTAC, genetics-gtac@email.wustl.edu

- Hope Center DNA/RNA Purification Core, Carlos Cruchaga, PhD, Director (cruchagac@wustl.edu)

Collaborate with any lab with wet bench activity.

Approximate Costs

- $200 + $100/sample (GEiC)

- $16/sample (Hope Center DNA/RNA Purification Core)

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Need to make decisions on what brain areas to investigate, etc. Confirm appropriate decrease in expression levels or mutation-related change.

iiib) Confirm protein level – western blot or immunofluorescence.

This step will inform is the mutation alters gene expression at the protein level. To determine level of overall protein made, immunoblotting, specifically a western blot, can be used here along with pixel-related image quantification to derive protein levels in the full tissue. For both loss-of-function “knockout” mice or point mutations, it is important to check that protein levels look normal or test the hypothesis based on what is expected to occur with the point mutation. For loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutations, this step will validate if the function was altered in the correct direction. It is also potentially informative, particularly for point-mutations, to confirm protein expression spatially using immunofluorescence (IF) or immunohistochemistry (IHC). This will allow the Investigator to determine if the normal subcellular location of protein is altered by the presence of the point mutation. For loss/gain-of-function mutations, spatial location of protein can provide further information how the protein is altered across the brain regions. In situ hybridization (ISH) is a possible alternative if a decent antibody to the protein of interest does not exist. Immunofluoresence and/or histochemistry services may be available through the IDDRC Neuropathology Subunit (NPS) (excluding western blots). Alternatively, these assays will need to be performed by a molecular biologist in the Investigator’s lab or a collaborating lab.

Contact

- Kevin Noguchi, PhD (noguchik@wustl.edu)

Collaborate with any lab with wet bench activity.

Approximate Cost

$45/hr, total varies based on individual project needs (NPS)

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Need to make decisions on what brain areas and/or cell types to investigate, etc. Confirm appropriate decrease in protein levels or mutation-related change.

iiic) For conditional models, validating Cre-responsiveness.

Conditional models include a small sequence of nucleotides called lox P sites flanking the locus of interest or configured to recombine the locus to turn on or off the mutation. The excision of the locus or the recombination of the sequences occurs in the presence of Cre recombinase. To validate the conditional model works as intended, Cre recombinase can be introduced via Adeno-associated viral (AAV) injections into the tissue (i.e., for brain, by the Hope Center surgery core) or by breeding to a Cre-expressing mouse line. Then, tissue can be genotyped for presence or absence of mutation/locus. Further, steps iiia and iiib can be completed to quantify RNA and protein levels in whole tissue or IF/IHC for spatial protein confirmation. The injections will likely need to be performed by a molecular biologist in the Investigator’s lab or in a collaborating lab with wet bench experience in this area. Then one of the Core facilities listed above can be used for the downstream assays to confirm gene expression changes. Cre recombinase AAV can be obtained from the Hope Center Viral Vectors Core.

Contact

- Viral Vectors Core, Mingjie Li, PhD, Coordinator (lim@wustl.edu)

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Decide the Cre promotor. Need to make decisions on what brain areas to investigate, etc. Confirm appropriate decrease in protein levels or mutation-related change.

4) Phenotyping.

Once model is established and molecular function is validated, the Model Systems Core (MSC) within the IDDRC@WUSTL offers many Core services for phenotyping IDD-related mouse models. The Animal Assessments Unit (AAU) within the MSC comprises the Animal Behavior Subunit (ABS), the Neuropathology Subunit (NPS), and the Neurophysiology Subunit (NPhyS), and the Developmental Neuroimaging Core within the IDDRC@WUSTL houses the Animal Imaging Unit (AIU). These core units offer a variety of services to comprehensively phenotype an IDD model.

Consultation is provided by MSC Directors and Unit/Subunit leaders to assist the Investigator in designing the phenotyping study based on clinical features. Details of services offered through the IDDRC@WUSTL Cores can be found here: https://iddrc.wustl.edu/core-facilities/. All Core Units/Subunits have existing, ongoing relationships and collaborations that will aid study design. In addition, cross-core data sharing will motivate assessments based behavioral or mechanistic findings.

Contact

- Karen O’Malley, PhD, Co-Director (omalleyk@wustl.edu)

- Susan Maloney, PhD (maloneys@wustl.edu) – Consultation for appropriate phenotyping workflow

Behavioral Characterization.

The ABS offers an array of IDD-specific behavioral tests and provides pre-study consultation with investigators to discuss issues such as sex effects, background strain, littermate controls, non-behavioral influences on performance, experimental design, and statistical power. Consultation will include recommending certain tests for specific models and cost estimates for the work involved, as well as referrals to other relevant cores. The ABS offers over 45 individual assays across several behavioral domains, including learning and memory, motor/sensorimotor functions, avoidance/anxiety and motivation, social behaviors, sensory functioning, depression-like behaviors, repetitive/restricted behavior patterns and cognitive flexibility. ABS leadership will help design a study of assays to survey a variety of behavioral circuits/research domains or a focused characterization based on patient phenotypes. It is recommended to contact directors early (e.g., when planning breeding of the cohort) for preliminary consultations on sample numbers, ages ranges, scheduling, and other design considerations.

Contact

- Susan Maloney, PhD, Leader (maloneys@wustl.edu)

- Carla Yuede, PhD, Co-Leader (yuedec@wustl.edu)

Approximate Costs

$45/hr, total varies based on individual project needs

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Provide clinical features to ABS leadership for clinically-relevant study design.

Neuropathological Assessment.

The NPS provides consultation and services to investigators characterizing animal models of IDD in basic histopathology approaches, immunohistochemical methods, and quantitative tissue analysis. Basic histopathology approaches for light microscopic evaluation include perfusion fixation, embedding, sectioning and staining of CNS tissues. Additional procedures offered include DeOlmos cupric silver staining, and in situ hybridization. The NPS has experience with a wide variety of immunohistochemical methods that can be used to identify cellular consequences of the mutation in both the developing and adult brains, as well as disrupted developmental processes such as neuronal proliferation, migration, or apoptosis. In addition, The NPS also provides ultrastructural analysis of pathological changes in the developing brain as well as quantitative tissue analyses. The NPS will develop additional approaches as need arises, and also provides investigator training in these methods and in research design, data analysis and interpretation.

Contact

- Kevin Noguchi, PhD (noguchik@wustl.edu)

Approximate Cost

$45/hr, total varies based on individual project needs

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Need to make decisions on what brain areas and/or cell types to investigates, etc.

Electrophysiological Assessment.

The NPhyS offers consultation and services for a wide range of in vivo and in vitro electrophysiology assays of rodent models of IDD. These include video-EEG monitoring to assess seizures and EEG background abnormalities, seizure threshold testing, polysomnograms for sleep characterization, somatosensory evoked potentials to quantify sensory abnormalities, microelectrode array recordings to assess network activity, and whole-cell patch clamp recordings in cultured cell and brain slices to gain mechanistic insights into learning deficits and epilepsy.

Contact

Michael Wong, MD, PhD (wong_m@wustl.edu)

Approximate Cost

$25/hr, total varies based on individual project needs

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Work with NPhyS leadership to determine assays for clincally-relevant study design.

Neuroimaging.

The Animal Imaging Unit (AIU) provides assistance with animal-specific imaging methods, including anesthesia, restraint, scanner operation, and surgical techniques. Using advanced MRI techniques, the AIU can assess brain structure including presence of macro- or microcephaly and alterations in ventricular size via whole-brain MRI, as well as integrity of white matter and myelination using DTI to measure axial diffusivity, radial diffusivity, and fractional anisotropy.

Contact

Joel Garbow, PhD (garbow@wustl.edu)

Approximate Cost

$105/hr scanner; $60/hr animal handling; $60/hr analysis; total varies based on individual project needs

Clinician/Investigator Decision

Need to make decisions on what brain areas to investigates, etc